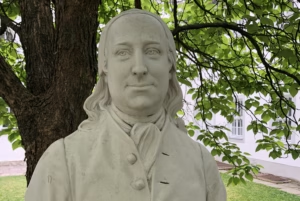

Count Zinzendorf – A Friend of the Jews

Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf – count, vicar, and landowner in Herrnhut – in the 18th century became the founder of the Moravian movement, a pioneering force in world missions and the initiator of 100 years of continuous prayer. They sent over a hundred missionaries throughout the globe and combined this with a deep respect for the Jewish people and God’s plans for Israel.

Bust of Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, in Herrnhut where Herrnhutism started, between the church’s parish hall and the bell tower. Photo: Jan Mathys

Alarge group of John Huss’s followers in Bohemia – Huss himself was burned at the stake in 1415 – were persecuted during the centuries after his death. Some of them fled to Germany in search of refuge, and Count Zinzendorf, who owned large estates, offered them shelter on his land. In this way, a movement arose that would become groundbreaking in church history.

The background to this awakening around Jesus’ atonement, the mission mandate, and Israel’s place in God’s plan was the availability of the Bible in the people’s own language. Theologian John Wycliffe released the first known complete translation of the Bible into English in 1382, and Johannes Gutenberg mass-produced the first Bible in 1455 – although in Latin. In 1466, before Martin Luther was even born, Johannes Mentelin printed a High German vernacular Bible in Strasbourg.

Zinzendorf added prayers for Israel within the community, and for the first time in the entire Western Church, intercession for Israel became a regular part of the liturgy. The prayer offered was that God would “restore the tribe of Judah in its time and bless its firstfruits among us.”

Respect for Jewish Roots

Zinzendorf also introduced Yom Kippur as a way to remember the Jewish roots of the faith, and even attempted to eat kosher food to make it easier for Jews to live within their community. He criticized the Western Church for adopting the name “Easter” (Ostern in German) instead of keeping to the original “Pasch” which is closer to Pesach the original name of the holiday.

The preferred Passover meal in many Moravian households throughout the 19th century was lamb, in reference to the Passover lamb that was slaughtered during the Exodus from Egypt.

Zinzendorf made several attempts to establish a Jewish Kehila (congregation or community) and arranged marriages between Jewish-Christian couples according to Jewish rituals, even though not many Jews came to faith in Jesus.

The Messianic organization One for Israel describes on its website “at least one Jewish family that joined the Moravian movement, whose descendants later became missionaries to Tibet — and there were likely others. But many non-Jews were also impacted by this remarkable movement and the gospel they offered.”

Respectful Talks

In 1739, Count Zinzendorf anonymously published a small book containing seventeen fictional dialogues. The main character likely represents Zinzendorf himself, and the dialogues portray conversations on various religious topics that arise during his journey through life. Among the seventeen dialogues are two chapters that depict encounters with people of the Jewish faith. One meeting with a Jewish merchant discusses the spiritual condition of the Jewish people, followed by a conversation between the book’s main character and a Jewish scholar, mainly revolving around the question of whether Jesus is the Messiah.

“Although the traveler seeks to persuade his Jewish dialogue partner of the truth of the Christian faith, their debate is surprisingly thoughtful and courteous, concluding in an open manner with mutual expressions of goodwill. The two dialogues depict a balance between sympathy for the Jewish people and insistence on Christ’s messianic significance — a representation of Zinzendorf’s overall approach to Judaism and the Jewish people. There, Zinzendorf strongly affirms the Jews as God’s chosen people who continue to play a central role in God’s redemptive history… Since God is faithful to His covenant with His chosen people, Christian believers have no reason to despise or mistreat the Jews. Rather, they are called to treat them fairly and to show them due respect, precisely for their ancient Jewish faith,” writes Dr. Peter Vogt in Journal of Moravian History No. 6, 2009, describing how Zinzendorf’s “position stands in stark contrast to the unfortunate currents of Christian antisemitism that contributed to the rise of Hitler and the Holocaust.”